I Went to Bethlehem to Find My Father

The author's grandmother in Japan in the 1930s, awaiting passage to Shanghai to escape the war. All family album photos courtesy of Liza Foreman.

We're kicking off 2015 in search of adventure. And here's a great one from Fathom contributor and globetrotting journalist Liza Foreman. Bethlehem: Road to Palestine, her new Kickstarter project, will be a memoir about her paternal grandparents, textile merchants who lived all over the world in the 1930s and 1940s, as well as family characters like her great grandfather Giris, a governor of Bethlehem, and a great aunt who ran off to become a nun (after rejecting Lawrence of Arabia's marriage proposal). Liza's journey that will take her to Bethlehem, Santiago, Bombay, Kobe, the Sudan, and Khartoum. (Clearly, she inherited her wandering ways.) This is how the story begins, with a search for her father.

In the spring of 1988 during the First Intifada, I took a bus from Jerusalem to Bethlehem to find my father. Soldiers squatted on abandoned shop fronts with metal cages pulled around their faces, rifles at hand. They stared suspiciously as I, a waiflike English girl all of seventeen, and my friend alighted from the bus to wander the barren streets and disappear into the dust.

"Please don't go," my mother had pleaded from England.

But there was no stopping me. The locals, mistaking us for Israelis lost in this Arab enclave, stood on their balconies and hissed. We continued until we found a deserted gift shop where a man dressed us in traditional costume as we sipped mint tea.

"Where can I find Farad Mattan?" I asked.

"He lives above the Seven Seas restaurant," he said.

My father, a Christian Arab from an old, wealthy Bethlehem family was well known around these parts. He had been educated in London where he had left my English mother and I when I was two. "He would have been a second-class citizen here, disinherited by his family for a child born out of wedlock," she would explain to me. "He was always going home."

My mother had married then remarried again. Farad broke off contact with us when I was three. He said it was best to stop sending the photographs and letters.

But an English judge had ordained that I must be told, and I always knew about him. At sixteen, after a tumultuous childhood, I had attempted to telephone this stranger from a call box at school. The line was dead.

A year later, here I was, in Israel on an exchange program. I stood in the street and rang his intercom. A boy answered.

"Please tell Farad that Liza is here."

Silence. No answer for half an hour. My friend and I kicked stones in the streets and were about to give up when the same voice said, "Please come in."

At the top of the flight of stairs, a young boy (my brother, it turned out) ushered me into an opulent living room filled with grand pianos and chandeliers, English magazines and silk cushions.

For the first time in my life, I saw the man that was my father.

He walked in and sat calmly in his fine slacks and shirt and played with his daughter (my sister), who ran into the room. "How are you?" he asked. "How's your mother? How is your father? Your sister? Are you happy? Do you need anything?"

"I don't need anything," I said. "I just wanted to get to know you."

We spoke politely for half an hour, then he arranged for a driver to take us back to Jerusalem. "Tell your people that we are starving. We have no food, no work, no water on The West Bank," said his driver.

Two years later on a trip to Israel, I went to meet my father again. His wife met me at the King David Hotel in Jerusalem. "Farad is a man who sees things in black and white," she said. "Because he did not grow up with you, he cannot get to know you now."

Then he came in and said the same thing. They left me their number in case I needed help.

Years later, my father helped me with money for a PhD, to buy the then-aspiring reporter a computer to pursue her dreams. On occasions when I asked, he would send a check. No letter. No other contact. Nothing more.

A few years ago, my rage grew and my despair. I went into self-destruct mode. I had some sort of desperation for him to finally love me and care for me, give me what I had been denied — the top education my siblings had with grand homes and jobs waiting for them. I slept for three nights in a beach hut as the Atlantic Ocean crashed to shore in the dead of night, at my lowest point, penniless with no way to get home.

But life propelled me forward and the rage poured out in emails to Farad. Then curiosity met his silence, and I started to spend time on the internet, researching his life. I found photos of him at his daughter's wedding, at the local university, and then a family tree. Through this, I discovered that I had three siblings. I found them on Facebook. Maybe they would want to get to know me?

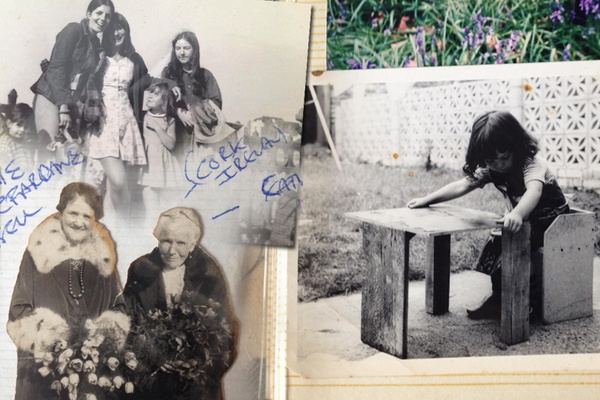

Images from Liza's family photo albums.

I couldn't bring myself to find out. Instead, I blurted out my story to a Palestinian film director I was interviewing after the Sundance Film Festival this January.

"Do you know this man? I asked, knowing that he was well known in his community. "What do you advise?"

I was holidaying on the Amalfi Coast in Italy this summer when the Facebook message arrived. "Looking for you," it said. "Farad is my uncle. I heard your story and I would like to know more."

If Farad was her uncle, this person was my cousin. What's more, I realized I had once interviewed her in Dubai.

A miracle had occurred. My new cousin, also a film director, had been looking for me for five years, she said. Slowly it began to emerge that beyond the wall which cut through my father's heart, there was a whole family of people who wanted me — a previously unimaginable thought. She began to tell me our family history via email.

Our people were textile merchants who had gone from Bethlehem to Japan and then India, where my father was born, and then the Sudan and England to set up shop before returning to Bethlehem. The kids had been schooled everywhere from Alexandria to London, where my father was sent to a Catholic boarding school. Like me, my people were wanderers and world travelers.

"I'm getting married in North Carolina. Would you like to come to my wedding?" she asked. "He's not coming." She wrote again, "My mother and father are so excited that we have found you. What do you think if we just introduce you during the event?" She did not know who knew what.

Two months later, I was on a plane from Los Angeles to North Carolina. I got to my hotel at 10 p.m. and called my aunt with great anticipation. Thirty minutes later, I saw a group of people hugging in a circle in the parking lot in the in the dark and sweltering heat. They hugged me one by one. Looks of bewilderment on their faces, emotions both happy and sad.

My aunt told her two other children — more new cousins — who I was. They had no idea I was coming or if I really existed.

"I feel like I know you," said one, in a daze.

She did. She had played with me as a child when my father was too scared to tell her or her mother who I was.

If only they had. With looks of total wonder and shock, we talked into the small hours. The next morning, my aunt called and said she would bring over her brother, my uncle, and tell him. "It is the only way to do it," she said. In he walked, unaware of what was about to happen.

"This is Liza, Farad's daughter," she began.

He did not register and sat down quietly. His wife began to cry. His daughter looked on in amazement. "Give me a second," he said.

My father had always kept me a secret. Many in his community had heard rumors or whispers following my trip to Bethlehem and through an outraged family friend. He sat in the corner stunned. We began to speak slowly. He had added me to their family tree, he said, when he had first heard of me. His wife cried.

"Did you know?" I asked.

"No," she said. I had seen these people on Facebook but didn't know they were relatives.

"We wish you had contacted us. My father should have known," my uncle said of the man everyone had been afraid to tell.

Liza, on left, meeting her new family.

My other cousins wiped their eyes in the background. New aunts and uncles pottered around making cups of tea. Family friends and relatives arrived, and each was told in turn. One was one of my father's closest friends. Others were friends of his children. That night at a welcome dinner, more family members or close friends who had left Bethlehem for the United States and Europe were introduced. Some were startled. Others went into shock. Tears came to their eyes. Guests came up to meet this figment of their imagination, this rumor, this ghost come back to life. The love that poured out began to melt the pain from the silence in my father's heart.

They told me about family traits. Chocolate cravings. Wanderlust. Whispers from bankers who had seen checks sent out. Proof I existed. Things they had heard. They embraced me with open hearts. They hugged me and walked around with me, holding me like a sacred child. They ferried me back and forth and told me stories of their lives.

"Great Uncle Habib (Harry) was once the richest man in England, the owner of nine textile factories," my uncle explained. The following day the story was amended: "Maybe not the richest man, but a very important man." My great grandfather had been the governor of Bethlehem. A great aunt had almost married Lawrence of Arabia. (He proposed.) Family records kept in the Church of the Nativity indicated that my ancestors originally came from Denim, near Lyon. My uncle liked to joke that they tried to get the Crusaders to wear jeans for their trip to the Holy Land.

After four days, I flew home and cried for a week. Emails began to flow. More relatives came out of the woodworks. I was no longer alone. I had family from Chile to Jamaica and across the United States. I emailed one of my new cousins.

"We have all had an emotional week," she said. "We are floored. No one could understand why he would do this. We love you and we are glad we have met you now."

I called my adopted father in England. "We all missed the point," I said. "There were people, my family, out there with beating hearts and they wanted to know me."

But my excitement was soon muddied by sadness. A month after the wedding, despite multiple emails and phone calls from his relatives, my father and his children remained silent.

BACK THE PROJECT

Get more information and support Liza's project on Kickstarter, Bethlehem: The Road to Palestine.

BUT WAIT, THERE'S MORE

In Fevered Pursuit of My German Ancestors

A Daughter of Exile Goes Home to Cuba

When You Travel Alone, You Belong to Everyone